Jean-Adrien Philippe was granted the Brevet n°1317 in 1845 concerning a keyless winding mechanism, avoiding the need of easily lost keys. He then went on to be the second name behind the Patek-Philippe brand. Other inventors, mostly forgotten, were also active in the 19th century: Charles Lehmann also patented a keyless system in the 1860s, obviously less successful but his system can be found in watches between 1860 and 1890.

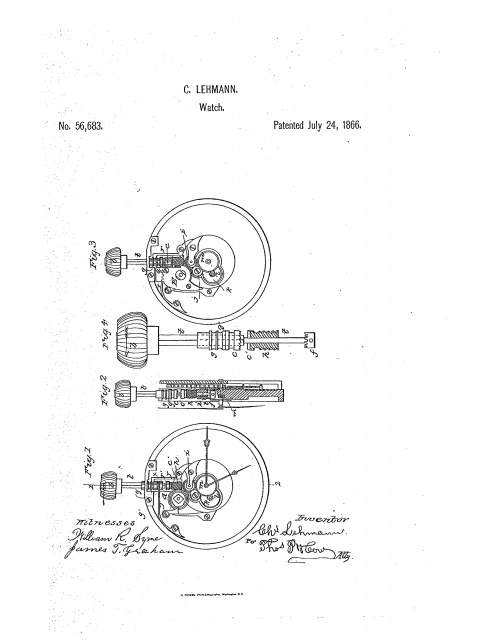

It seems that the Lehmann system was patented in France and in the USA, at least. The US patent has a nice drawing of the complex keyless works. The latest version of the system is quite modern, allowing both winding and time setting with only the crown. Most watches used either a key or a simple keyless system with a pusher to be depressed while setting the time.

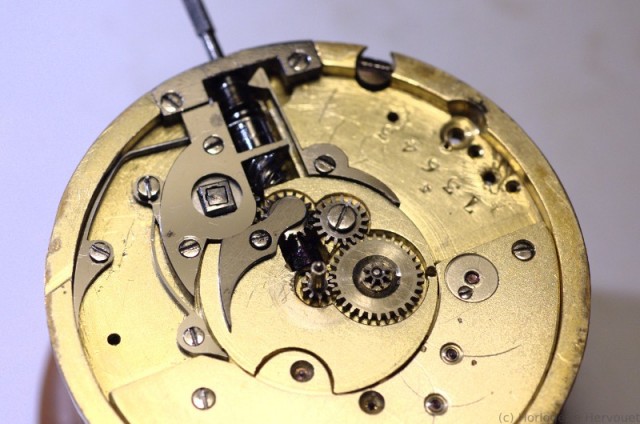

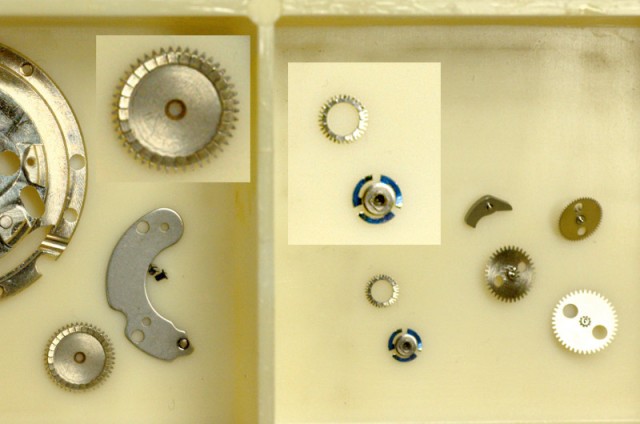

Most of the system is located behind the dial, and looks quite complex:

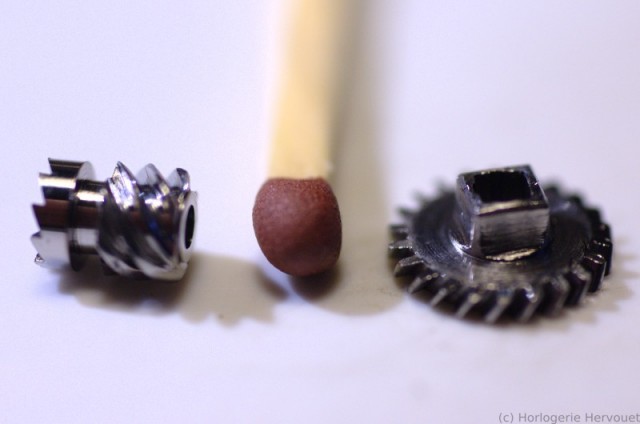

The stem assembly alone is remarkably complex, all those parts must have been very costly to produce.

The main difference with Philippe’s system is the wormwheel.

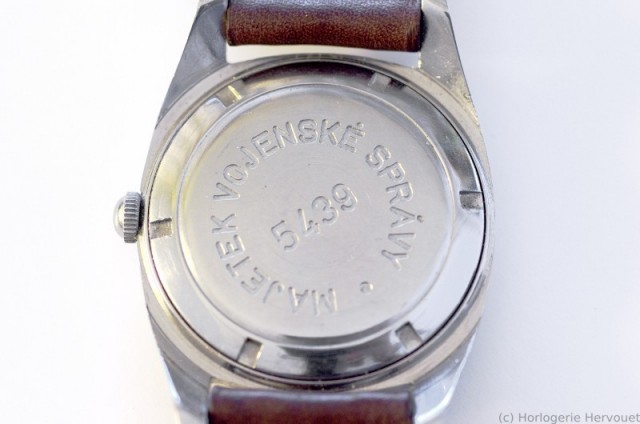

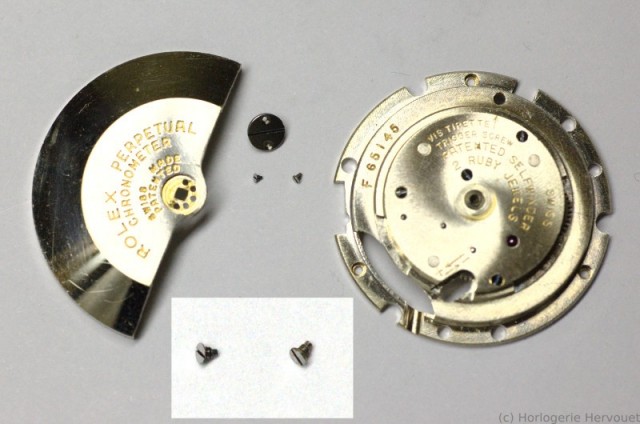

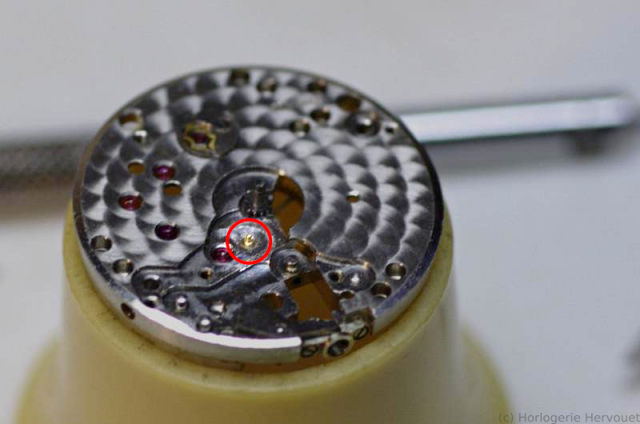

This particular watch had a long life: lots of service marks in the caseback, the engravings on the silver case are almost worn off. Somebody not very talented did some damage: destroyed screws here and there, and the Maltese cross had been violently torn off (it cannot be realistically replaced), the mainspring barrel has to be reshaped. But the most problematic repair is hidden in the keyless works: the small screw fastening the pinion at the end of the stem is loose, the threads have been thoroughly stripped and the hole has been reamed! The pinion being loose, the wear of the gears is important but the system still works…

The clean way to repair this mess is the following: rethread the stem, and drill the pinion so that a slightly bigger screw can pass trough. Of course, the pinion is in tempered steel, so a blowtorch and some quenching afterwards will be involved.

Next, a custom screw is machined:

The patent number is proudly engraved in the baseplate:

Patent number on the baseplate (the Maltese cross on the barrel was torn off in a previous “repair”)

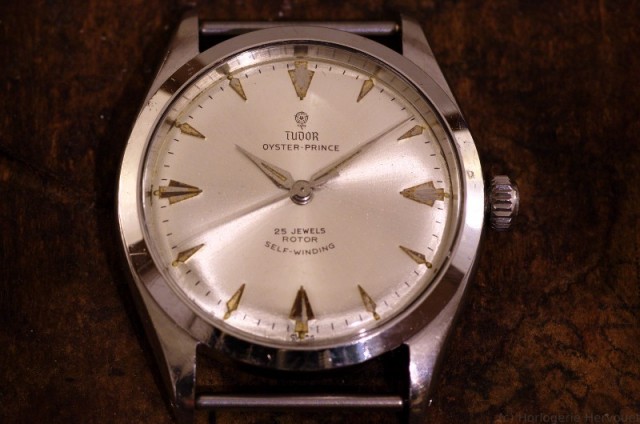

More than 130 years old, and still ticking!

The dial and hands have been replaced at some point, but the silver case is still marked “Lehmann breveté SGDG”.

Sources:

watch-wiki.org

Watchuseek forum